On medium-sized questions in neuroscience

Featuring sensory substitution, fading percepts, and hyperacuity

We are living through a great flowering of machine intelligence spurred by artificial neural networks. Despite the name, the neural networks grabbing headlines these days have only a distant kinship with biological neuronal circuitry. I like to say that an artificial neural network is as similar to a real brain as a car is to a horse. 1

Having said that, GPT, Midjourney and the other marvels of modern machine learning must give many neuroscientists — and particularly my fellow computational neuroscientists — a kind of envy. How is it that a bunch of engineers who probably can’t name more than four subcortical structures created software that emulates, and sometimes surpasses, the abilities of humans? Wasn’t that our job?

I think many of us will agree that the answer to that last question is no.

Given the tech and sci-fi bias of a lot of pop culture, it can seem as if imitation of human intelligence is the primary goal of computational neuroscience, if not of the entire field. Other closely-related goals are cognitive enhancement and technology-assisted immortality.

I think everyone interested in the brain — both researchers and the wider public — should pause to consider the sheer variety of interesting questions one could ask about brains and behavior. I think most people will find that only a fraction of these questions overlap with the ones being asked by researchers in AI and ML (or by people who want their favorite sci-fi concept to become a reality).

Large, Medium, and Small Questions

It is natural to assume that all neuroscientists are working to answer one big question: How Does the Brain Work?

I don’t deny this, but I think “how does it work” is far too vague a question. It skirts dangerously close to philosophical questions that tend not to get answered: they just get re-asked using the latest terminology. What is consciousness?2 Do we have free will? Can we upload our minds to the Cloud?3

At the other extreme from “How Does the Brain Work” we find a host of questions that are decidedly not vague. When you wander through the poster hall at your first Society for Neuroscience conference, you realize the sheer number of hyperspecific questions that can be asked. And at least partially answered, usually without any philosophical chin-scratching. Here are some parody poster titles4:

“Effects of Boxytocin Antagonist Amatoran on the Grooming Behavior of Adolescent Mice Previously Administered Cyclocetraline-3”.

“Optogenetic inactivation of FK4Tw7g-expressing neurons in the substantia nomenclatura pars ridiculata triggers aggressive chewing in prairie stoats”

“Administration of anantamine to humans with nonspecific annoyance disorder leads to global aleph-nought synchronization”

Between the unanswerably broad and the squint-inducingly technical, there lies a rich zone of medium-sized questions that I think are both scientifically well-posed and of general interest. Also, they radiate outwards, spurring more specific experimental questions as well as philosophical speculations. Instead of moving in a “top-down” direction (a progressive increase of detail) or in a “bottom-up” direction (a progressive increase of abstraction), sometimes we can adopt a “middle-out” approach, widening and narrowing the scope of our questions with a flexible rhythm.

Sensory substitution — new senses for old

The BrainPort is a video camera attached to a multi-electrode “lollipop” that sits in the user’s mouth. With the help of this contraption, visually impaired people (or blindfolded journalists5) can learn to ‘see’ with their tongues.

Sensory substitution, also known as sensory remapping, seems to work quite well, but we don’t know how — which means we can zoom in with more specific questions. How do the signals in the tongue percolate through the brain to enable a visual experience? Which anatomical pathways are involved?6 What kinds of training are required? Can chemical or electrical manipulations modulate the effect?

The sensory substitution phenomenon can also point towards increasingly philosophical questions about perception. For example, do the signals from the tongue need to be routed to the visual cortex in order to trigger ‘seeing’? Or might these signals trigger ‘vision-manifesting” patterns wherever they are sent, as a result of their interrelationships rather than their location? Conversely, are there types of patterns we could send to the visual cortex that are not subjectively experienced as vision? Could we invent entirely new senses? And can we ever establish if tongue-generated vision is ‘like’ normal vision? What is it like to be a light-taster?

Fading percepts — do we perceive states, or changes?

The eye is often compared to a camera, but this creates a very misleading impression: that a sequence of static snapshots of the world is sent from the eyes to the brain. It has been known for decades that if we stabilize an image so that it is stationary with respect to the retina of the eye, then visual experience fades.

The exact mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are still not fully understood. One idea is that microsaccades — tiny eye movements that occur even when we think our gaze is fixed — evolved in humans and some other animals as a way to keep the world visually present. By contrast, it seems as if some animals only sense external changes in the world. Frogs are exceptionally good at flicking their tongues at passing flies, but they will starve to death when surrounded by dead flies — they simply don’t see them!7

But experimental work8 suggests that microsaccades might not be the whole story. In the lab, microsaccades do seem to allow images to reappear when they start to fade, but this occurs in conditions where the subject’s head is fixed, so they can’t move anything other than their eyes. But in natural conditions the head and the whole body can move. When the world lacks movement, we can just supply our own. But how are these movements calibrated? How do animals ‘decide’ when and how to move? These are testable, specific questions.9 But we can go in the other direction too.

Stabilization-induced image fading suggests to me that vision is a bit like the sense of touch: if you’re blindfolded, it is much easier to identify a texture by moving one’s hands over it rather than just leaving the hand stationary. Perhaps all senses work a bit like this. Perhaps consciousness is not about “snapshots” or “samples” of the state of the world, but about differentiating signals with respect to space and time, and then integrating the changes that happen to be useful in a given context. And perhaps raising attention to a very subtle process involves a form of targeted self-motion, or even virtual motion.

Hyperacuity — when the whole perceives more accurately than any of the parts

Any sensor used to pick up signals from the world has physical limits. The resolution of a CCD camera is constrained by the density and light sensitivity of its pixel sensors. To improve resolution, pixel density must be increased, so each pixel must be made smaller. If the pixels themselves are large, or sparsely arranged, there is not much that a standard10 digital camera can do downstream to improve the resolution of the final image.

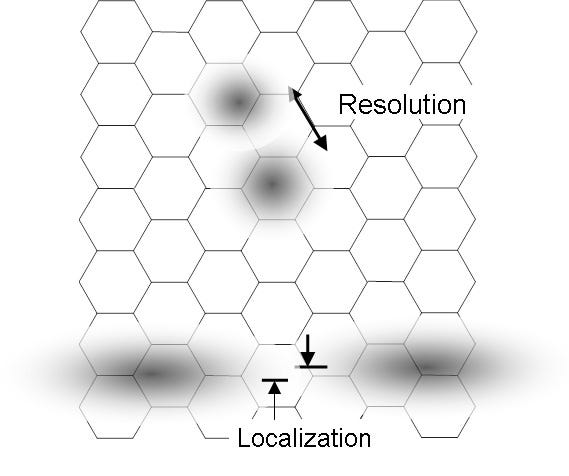

But this is not the case with human vision. As with a camera, human vision is constrained by its low-level sensors: the rod and cone cells of the retina. The ability of these cells to discriminate adjacent patterns of light can be measured. This is known as acuity and is the biological analogue of pixel resolution: it determines the smallest visual object that we can see. But there is a type of visual information that humans can extract from the retinas that far exceeds the constraints of acuity: we can tell if two line segments are aligned with an accuracy that is up to ten times the acuity of individual cone cells in the retina. So the abilities of the organism as a whole exceed some of the limits one might expect if the visual system worked like a camera. This is known as visual hyperacuity: we can localize patterns of light that are separated by distances smaller than individual retinal cells can “distinguish”!

Visual hyperacuity is sometimes called vernier acuity, because it is the basis for our ability to use vernier callipers and similar devices to measure length: we are exceptionally good at telling if two edges are aligned or not.

We can measure how good humans are at this sort of thing, but we still don’t have a very good idea of how we achieve this. So the topic generates concrete questions for experimentalists and computational modelers. In what way do neurons cooperate to overcome their individual limitations? And where in the brain does this cooperation occur? Many related micro-questions are being asked; hyperacuity seems to occur in other sensory systems too.

And once again, we can go in the other direction. How is it that biology enables forms of synergy that differ so radically from our engineered solutions? The brain forms a loose hierarchy — so loose that the term “heterarchy” is probably more appropriate. Could the fuzziness of “levels” of processing in the brain somehow enhance performance, despite our experience that in tech, fuzziness tends to degrade performance? How is it that parts can get together to form wholes that display novel capabilities?

Meso-scale abstraction

For a few years I used to answer neuroscience questions on Quora. It was a great experience: sometimes people asked questions about the cognitive and microbiological benefits of very specific foods or activities. And of course there were countless permutations of the classic big questions about life, the universe and everything. But my favorite questions were medium-sized. I learned a great deal by attempting to answer them. Here are a couple of favorites:

I think asking questions like this requires a transformation of attention: you can’t be too focused on high-res details, nor can you just stop at rough sketches. Speaking of sketches, something like this seems to have happened at the dawn of impressionist painting. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and even John Singer Sargent11, began to experiment with their attention, finding a spot between objective verisimilitude and solipsistic abstraction. They found medium-sized questions within the space of art.

As with painting, medium-sized scientific questions require that we find intermediate levels of abstraction: the fertile middle ground12 between hard-to-follow detail and metaphysical vagueness. This zone is a great starting point for exploration. I hope to visit more such questions in this newsletter.

Notes

On the similarity of artificial neural networks (ANNs) to real brains. I’ve presented my opinion as if it’s obvious, but it is actually contentious. Some people think that ANNs do give us insights into how biological brains work, whereas others disagree vehemently. I am on the side of the latter: I suspect that in the long run, we will find that any similarities between ANNs and brains arise because of (1) generic properties of neuron-like integrator/detector units arranged hierarchically, and (2) statistical properties of the tasks and the datasets, rather than the brain per se.

A recent paper in Behavioral and Brain Sciences argues that ANNs have been oversold as models of biological visual processing.

Bowers, Jeffrey S., Gaurav Malhotra, Marin Dujmović, Milton Llera Montero, Christian Tsvetkov, Valerio Biscione, Guillermo Puebla et al. "Deep problems with neural network models of human vision." Behavioral and Brain Sciences (2022): 1-74. [link]

Also, here’s an old Quora answer I wrote on the differences between artificial and biological neural networks.

Neuroscience and consciousness. In grad school I had a professor who described consciousness as the “c-word” and banned it from his lectures for being too vague. I elaborate on this here: Why Some Neuroscientists Call Consciousness the C-Word.

On mind-uploading. I for one do not think this is a meaningful, let alone feasible, concept. I elaborate here: Will we ever be able to upload our minds to a computer?

Parody neuroscience. I am poking what is hopefully some gentle fun at the dizzying array of experimental questions out there. I have immense respect for the painstaking work being done by experimentalists.

Seeing with the tongue. Here’s a great New Yorker article on the BrainPort. Sensory substitution was pioneered by the neuroscientist Paul Bach-y-Rita.

The anatomical basis of sensory substitution. While looking for an image of a BrainPort (the one used above), I found this paper:

Lee, Vincent K., Amy C. Nau, Charles Laymon, Kevin C. Chan, Bedda L. Rosario, and Chris Fisher. "Successful tactile based visual sensory substitution use functions independently of visual pathway integrity." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8 (2014): 291. [link]

“However, the use of sensory substitution devices is feasible irrespective of microstructural integrity of the primary visual pathways between the eye and the brain. Therefore, tongue based devices may be usable for a broad array of non-sighted patients.”

EDIT: A friend pointed out that frogs may actually be able to see the dead flies, but just prefer ‘fresh’ ones. But the literature does suggest the following:

“Animals lacking fixational eye movements, such as afoveate frogs and toads, may be incapable of seeing stationary objects during visual fixation.”

Martinez-Conde, Susana, and Stephen L. Macknik. "Fixational eye movements across vertebrates: comparative dynamics, physiology, and perception." Journal of Vision 8, no. 14 (2008): 28-28. [link]

Image stabilization and eye movements. Here is a paper that investigates the connections between microsaccades and image fading. The authors cite key historical studies.

Poletti, Martina, and Michele Rucci. "Eye movements under various conditions of image fading." Journal of Vision 10, no. 3 (2010): 6-6. [PubMed]

On microsaccades and attention. My friend Karthik Srinivasan and his colleagues at MIT have done fascinating work on the connection between eye movements and attention. Here’s a recent preprint:

Srinivasan, Karthik, Eric Lowet, Bruno Gomes, and Robert Desimone. "Stimulus representations in visual cortex shaped by spatial attention and microsaccades." bioRxiv (2023): 2023-02. [link]

EDIT: A friend (the same one!) pointed out that some new digital cameras use motion (“sensor-shift”) and/or interpolation to achieve “super-resolution”. This is not quite the same thing has hyperacuity though, since humans can perceive alignments that exceed the limits of the retinal cells. I wrote more about this here: Is the resolution of the human eye infinite?

Also see this:

If we consider the human eye operating principle equivalent to that of digital cameras, that would be emulated as a system of low sensitivity and poor resolution. However, it can by far overcome the sensitivity and image resolution defined by the size and number of its sensors thanks to an amazing feature: the visual hyperacuity. Given this fact, it seems logical to think that the human eye goes beyond the working principles of common digital cameras and should be given further consideration.

Lagunas, Adur, Oier Domínguez, Susana Martinez-Conde, Stephen L. Macknik, and Carlos del-Río. "Human Eye Visual Hyperacuity: A New Paradigm for Sensing?." arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.00249 (2017). [link]

On Sargent and impressionism. The Nerdwriter YouTube channel has a great new video on the artistic innovations of John Singer Sargent.

The middle ground. I am not saying that there is always a clearly defined ‘medium scale’ for every field or phenomenon: we can instead say that the detail-to-abstraction continuum can be relativized with respect to the goals and constraints of the question-askers. Another way to say this is that given a phenomenon, we should oscillate attention between one level “up” and one level “down” (if not more), regardless of how we slice up the levels.

It may well be that this level-fluidity is how the brain enables hyperacuity!

Perhaps we need cognitive microsaccades too?

The hyperactuity diagram is from Wikipedia. So is the vernier calipers gif.

Points if you spotted the obscure Sanskrit+mathematics pun in this post! :)